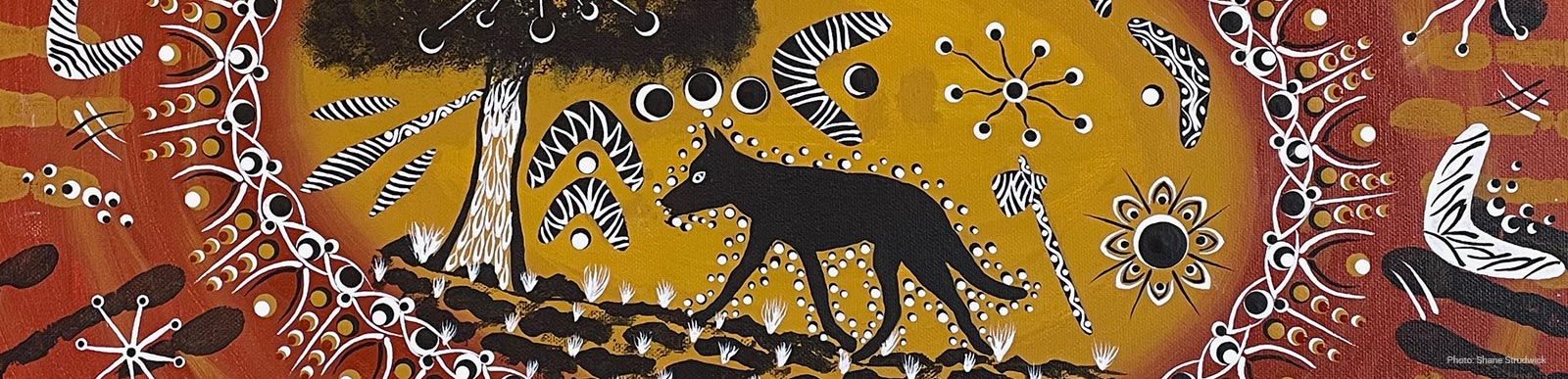

The largely waterless lands of the Corner Country were traditionally occupied by several Aboriginal groups. In the Milparinka area lived members of the Maliangaapa people, around Tibooburra, were Wadigalis and Wangkumaras.

A fundamental understanding of the land and environment helped Aboriginal tribes to survive, especially their ability to find and conserve water. Soaks and wells were dug in dry creek beds, holes gouged into the lower ends of claypans, and campsites established alongside creeks and waterholes. They carried water in bags of kangaroo skins, or in coolamons. Many Europeans, both explorers and early settlers, could not have survived without the help of the Aboriginal people.

Trade routes and tracks were established across the desert to the west, to the north and east to the rivers. Sturt recorded following one track for six hours, coming, in the end to a well full of water. Stone artefacts found in the Corner Country had their origins in quarries hundreds of kilometres away.

The settlement brought changes to life in the Corner Country. Pastoralists spread their flocks of sheep and cattle across the region and competed with local Aborigines for water, and for grazing land. Often there were serious and tragic consequences. In time, however, many Aboriginal people were employed on the newly formed stations and were able to co-exist with pastoralists on their traditional lands. Others moved to local centres such as Tibooburra where they lived on the fringes of the township.

In 1909 the Aboriginal Protection Act was implemented, and in 1936 the Aboriginal Protection Board acquired the powers to remove Aborigines from “undesirable living areas”. From Tibooburra, around 70 people were forcibly loaded onto trucks and taken to Brewarrina. Some found their way home to their tribal areas, but life for many was irreversibly damaged.

Across the Corner Country are many locations with traditional Aboriginal names, Milparinka and Tibooburra are just two.

Evelyn Creek | Read more >

Aborigines have lived in the area known as NSW for at least 45,000 years and traditionally there are more than 38 Aboriginal language groups. The Aboriginal heritage of each bioregion is described in bioregional overviews, except for those bioregions in the Western Division of NSW where the overlap of language groups required a broad description as provided in the following account by way of background information.

Aboriginal occupation of the Western Division

(This section is largely based on HO and DUAP 1996: Chapter 16 of Regional Histories of New South Wales.)

The NSW Western Division, effectively bisected by the Darling River, was traditionally home to around 15 major Aboriginal groups. Many of these groups lived along the rivers of the Western Division, the Barwon, Darling, Lachlan, Murray, Paroo and Warrego Rivers, which provided Aboriginal people with more reliable and plentiful food supplies than those people living away from the major rivers in the scrub country and mallee [1].

The Wiradjuri language group, whose homeland was traditionally centred on the area south of Cobar on the Lachlan River, reached their westernmost extent along the Lachlan through the Riverina Bioregion to the junction of the Lachlan and Murrumbidgee Rivers. Adjacent to this homeland in the north-west of the Riverina Bioregion and south-east of the Murray Darling Depression were the traditional lands of the Jitajita. The Kureinui people lived along the northern bank of the Murray and west to where the Darling joins, while further west were the traditional lands of the Maraura. The Maraura hunted over the border in the South Australian mallee each winter [1] and were also known as Wiimbaio [1].

The Barkindji people were predominant around the lower Darling, which they called the Barka, Barkindji literally meaning “Darling folk”. The homelands of the Barkindji extended from what is now Wentworth in the Riverina Bioregion, northward through the Murray Darling Depression Bioregion and into the Darling Riverine Plains Bioregion beyond Wilcannia [1]. Barkindji homelands were known to extend into Queensland via the Paroo due to the friendly relations they had with the Parundji people of the Darling Riverine Plains Bioregion (HO and DUAP 1996). The home of the Parundji was the banks of the Paroo River, although unlike the Murray and Darling River groups, they did not use the rivers for transport in bark canoes.

The mid-Darling was traditionally occupied by the Naualko people on the west bank near the Warrego junction in the Mulga Lands Bioregion. Further upstream near Bourke and Brewarrina, the Ngemba people occupied the east bank of the Darling in the Darling Riverine Plains, while the Baranbinja and Ualarai people lived on the west bank of the Darling in the Mulga Lands Bioregion [1].

The Darling River was a less reliable water source than the Murray and because of this the use of fishing equipment is more elaborate. The fish-traps built by the Ngemba in the river near Brewarrina provide a good example of the innovations by the local Aboriginal people in water management, as does the stone dam built by Aborigines just downstream of the Darling-Warrego River junction [1].

Other Aboriginal groups of the Western Division were not wholly reliant on the rivers, accessing them only in times of drought or extreme heat. From the Lachlan to the east bank of the Darling River was the homeland of the Barindji (not Barkindji) and the Wongaibon, and to the west in the corner country were further groups.

The Karenggapa people traditionally occupied the far north-west corner of NSW in the Channel Country Bioregion at the Queensland border [1]. The Maliangapa people occupied the area around the seasonal lakes south of Tibooburra and, like the Karenggapa, were more likely to travel north or west rather than join the people of the Murray-Darling on the rivers [1].

However, further south in the Broken Hill Complex Bioregion the Wiljakali people traditionally occupied the lands around Broken Hill [1] and visited the Barkindji people on the Menindee Lakes in the Darling Riverine Plains Bioregion each year.

Just as the majority of Aboriginal groups populated the areas close to water, early European settlement in the west began with the rivers, and so it was the Aboriginal people of the far west and mallee regions who survived the longest with little European disturbance. The Barindji people east of Menindee are one example, living their traditional lives into the 1850s without interruption.

The river groups such as the Barkindji were much less fortunate, losing their traditional lands and hence their existence as hunters and fishers as early as the 1830s. Although the Barkindji resisted European attempts to invade their country – and were, for a while, successful, they were soon to lose their rightful place in the landscape [1].

Once European settlement was well under way in the west, Aborigines on the Murray River began working on stations and were often responsible for the transportation of wool bales in their bark canoes along the rivers south to the Victorian markets [1].

The riverboat trade began on the Murray and Darling Rivers around 1853, at which time the lifestyles of the river people were disturbed irreversibly. Aboriginal people were then employed as timber cutters, the timber used as fuel to power the steamers’ boilers. When a steamboat, the “Gemini”, made its maiden voyage on the upper Darling in 1859, it soon encountered the Ngemba fish-traps at Brewarrina, which stopped its progress – but not for long. The traps were dismantled in part and by the 1870s, with the right water levels, steamboats could reach as far upstream as Walgett in the Darling Riverine Plains Bioregion.

Aboriginal men of the west were also employed as shearers and cattlemen on many of the stations during the 1860s and 1870s, while Aboriginal women were employed as domestic helpers in homesteads, sometimes bearing settlers’ children [1].

By this time – the 1870s – only the Aboriginal people of the most arid areas retained, for the most part, their traditional lifestyles. However, traditional lifestyles required mobility over large areas of the landscape to use the products which the Aborigines needed to subsist. The European presence did not allow this mobility and the range of the Aborigines was restricted to such an extent that there was no choice for them but to relinquish their traditional ways and turn to missions and stations simply in order to exist [1].

The struggles of station owners from the 1890s due to droughts and harsh conditions on the land also adversely affected the Aboriginal tribal groups of the west and as a result their populations rapidly declined. As they left the stations, Aboriginal reservations were created to provide them with accommodation, mainly in tents. These reservations came under the jurisdiction of the Aborigines’ Protection Act, 1909 at such places as Pooncarie (near Menindee), Milparinka, Tibooburra and White Cliffs.

The influenza epidemic in 1919 all but destroyed the remainder of the Aboriginal population of the west and those who survived were placed on a new reserve near Menindee in the 1930s. The remaining community of 70 Maliangapa people still living in their traditional corner country in 1936 was trucked east to Brewarrina against its will.

Reference: [1] Environment NSW